A Night To Remember is a 1955 nonfiction book by Walter Lord in which he interviewed some sixty Titanic survivors before using those recollections to vividly reconstruct and recount the last hours of that doomed vessel. I highly recommend the book to you. It’s a quick, but poignant, read at 150 pages or so.

For those of you with no inclination to buy the book, here is the Cliff Notes version of the destruction of that “unsinkable” ship more than a century ago around this time of year …

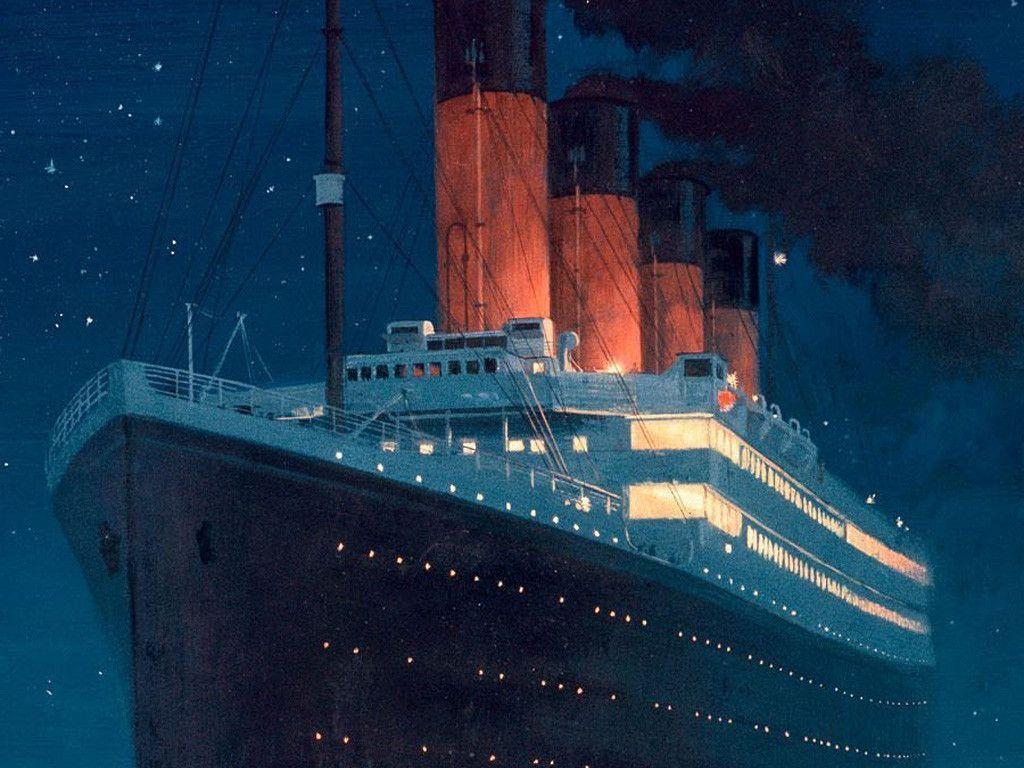

The Titanic set sail on April 10, 1912 from Southampton, England on its maiden voyage with 2,240 passengers and crew on board. It was the pride of the White Star Line and a hot ticket for those taking its inaugural journey across the Atlantic.

In 1898, fourteen years before the sinking of the Titanic, Morgan Robertson – the self-proclaimed inventor of the periscope and an American writer, published a novel called “Futility, or the Wreck of the Titan” about the “largest ever built” three screw (propeller) 800 foot long luxury liner capable of traveling at 25 knots an hour. In the novel, the Titan is full of rich passengers and in the course of the story the “unsinkable” Titan hits an iceberg capsizing the ship and killing most of those on board. More than a decade later, in the real world of 1912, the newly constructed Titanic was 175 feet tall (that’s about 17 stories high), 882 and a half feet long (equivalent to four city blocks), had three screws and could go 25 knots (about 29 mph). It too was full of rich people, as well as lots of other folks, and was heading across iceberg infested Atlantic waters on a course eerily similar to that taken by the fictional Titan fourteen years previously in the pages of a book. Morgan Robertson was a relatively obscure American writer, few people in the United States had read his novel about the Titan and virtually nobody in Britain had. After the events of April 14-15, 1912, people discovered the novel and wondered at Robertson’s prescience.

There were three classes of passengers: First Class, Second Class and Steerage. Most of us certainly would not have been First or probably not even Second Class passengers. In First Class were people like John Jacob Astor, who made his money in the fur trade, as well as Benjamin Guggenheim, a successful businessman and for whom the Guggenheim Museum in New York City is named. Also on board were Isidor Straus, the founder of Macy’s department store, Henry Sleeper Harper, owner of Harper’s Magazine, and millionairess Mrs. James J. Brown better known as “Molly” whose experiences were made into a hit Broadway musical “The Unsinkable Molly Brown”. The unfortunately named Archie Butt, President Taft’s military attaché, and Frank Millet, a famous painter and sculptor, were among the Americans on board. In addition to the First Class passengers were Bruce Ismay, the President of the White Star Line, and Thomas Andrews who was the managing director of the shipyard that built the Titanic. Both Ismay and Andrews were aboard the Titanic to iron out the kinks in the service on board as well as the actual mechanical operations of the ship during that maiden voyage.

There were employees on board of course. People like Fred Wright the Titanic’s squash pro (squash is like racquet ball and yes – the Titanic had a racquet ball court, a library, a gym, various entertainments like mechanical horses that passengers – both adults and children – could ride as well as a myriad of other perks and privileges of cruising). Professional masseuse Maude Slocombe and gym instructor (we’d call him a fitness trainer today) T.W. McCawley were also among the service employees on the Titanic. That’s in addition to the crew that included Captain Edward Smith, First Officer Charles Lightoller, First Officer William Murdoch, Lookout Frederick Fleet, Radioman Jack Phillips and scores of others.

Then there were the folks in steerage, mainly immigrants looking to come to America for opportunity. They included a “Mr. Hoffman” (not his real name), who appeared to be Czech, and Daniel Buckley, an American, as well as 26 year old Norwegian immigrant Olaus Albelseth who had a homestead in Perkins County, South Dakota waiting for him upon his anticipated arrival in the United States. We’ll get to the fate of these three gentlemen a bit later on.

The first few days were smooth and routine, until the night of April 14, 1912. Frederick Fleet was in the crow’s nest on lookout duty when he spotted something blacker than the surrounding darkness in the distance. He took a minute to confirm, but not much more than that. It was an iceberg, 100 feet high off the starboard bow of the Titanic. It was 11:40pm. He alerted the bridge, where First Officer William Murdoch had the watch and the con. Murdoch took immediate evasive action to avoid the berg but a ship the size of the Titanic takes some time to execute a maneuver and actually change the ship’s course.

The ship grazed more than struck the iceberg, but that was enough. The hole below the waterline was approximately 245 feet long. The compartments in the hold and engineering began to fill. Murdoch hit the switch on the bridge to close the bilge hatches and limit the damage. Then he sought out Captain Smith. Edward Smith was 59 years old, an experienced Captain who had been at sea for nearly four decades. This was his last trip as a Captain of the White Star line. He was due to retire after the Titanic’s return trip from New York. Smith complimented Murdoch on his actions and then went to the radio room to tell Jack Phillips to send out a “CQD” distress code.

The SOS distress code was first introduced to the international maritime community in 1908 but wasn’t in common usage yet. Neither CQD nor SOS are acronyms for anything other than to simply indicate help is needed and now. The British used CQD as a distress code, the Germans used SOE and the Americans NC. Radioman Phillips sent his CQD at 12:15am on April 15, 1912. He would later send an SOS as a final act of desperation.

It was a good news and bad news situation for the Titanic. Just 10 miles away, steaming the same direction was an American ship, the Californian, close enough to render assistance in under an hour. Thomas Andrews, the managing director of the firm that built the Titanic, knew the ship inside and out. After inspecting the damage, Andrews told Captain Smith that the Titanic had two or three hours to stay afloat. The ship was designed to limp along if four compartments were compromised, unfortunately five had been. They would fill and then spill over into the next compartment, with rising water levels throughout the ship similar to the effect of one domino being knocked over causing the rest to fall down. There was nothing to be done. No amount of damage control, heroic actions by the firemen and engineers down below could save the Titanic. She was doomed. It was time to get passengers off the ship.

The good news was the Californian was close enough for a rescue. The bad news was their radioman had gone to bed and turned off the set, so the Titanic’s distress calls went unheard and unheeded by those aboard the Californian. The Titanic’s distress calls did indeed reach other ships, just not the Californian. The Titanic’s sister ship, the Olympic answered and said she was responding to the distress call. The bad news was that the Olympic was 500 miles away. Another ship, the Frankfort said she was coming – good news? Not really, the Frankfort was 170 miles away. Meanwhile, the deck watch on the Californian saw the Titanic’s lights going out and thought the ship was encouraging its passengers to go to bed. Then the Californian saw the distress rockets from the Titanic but assumed the lights had gone out so that passengers could enjoy the fireworks display. Ah, the life of the rich and famous thought the envious deckhands on the midnight watch aboard the Californian. The Californian, stopped dead in the water because of nearby icebergs, remained blissfully unaware as the nearby Titanic was sinking more and more rapidly.

Also receiving the distress call was a British ship, the Carpathia. It’s Captain, Arthur Rostron, immediately responded although 58 miles away from the Titanic’s position. He changed course and headed north, towards the Titanic. The Carpathia was rated for a top speed of 14 knots, Captain Rostron managed to coax 17 knots out of her. He radioed the Titanic he was coming, but it would take up to four hours. Jack Phillips, the Titanic’s radioman, had been told by that time to abandon ship by Captain Smith. He refused, staying at his radio, sending and receiving messages until the rushing water nearly reached his knees. Phillips begged the Carpathia to hurry.

The Carpathia did hurry, dodging icebergs some of which were 200 feet tall. Captain Rostron was coming as fast as humanly possible. It just wouldn’t be fast enough for most of the passengers of the Titanic. From the deck of the Titanic, the lights of the Californian looked tantalizingly close but why weren’t they getting any closer? That was the desperate question of the passengers and crew of the Titanic as the doomed ship dipped deeper into the waters of the icy Atlantic Ocean.

I won’t bore you with the specifics but British maritime law at that time required the number of lifeboats on board a ship to be based on the footage of the vessel rather than on the maximum total number of potential passengers. The Titanic actually had more lifeboats than British law required. The Titanic’s lifeboats had a maximum capacity of 1178. The trouble was there were 2240 people aboard. It actually was a double tragedy because not only were there not enough lifeboats for everyone, but many of the lifeboats were not filled to capacity. For example, one lifeboat with occupancy for 40 was launched from the Titanic with only 12 souls aboard.

It was women and children first, but that didn’t mean “only women and children”. Some women refused to leave their husbands others were too terrified of leaving the seemingly solid Titanic for the relatively tiny, crazily swinging lifeboats. Some crew members bodily threw women into the lifeboats in order to save them. Men lied to their wives, saying they would get on the next lifeboat. First Officer Lightoller refused to let any men in lifeboats, firing a pistol at the “cowards” trying to board before the women and little ones. The aforementioned Daniel Buckley fell into a lifeboat having been jostled right off of the ship by panicked, frantic men. Mrs. Astor threw a shawl over his head to prevent Lightoller from removing him from the lifeboat. This was later turned, by the press, into Buckley masquerading as a woman to escape the sinking ship. Perhaps because of that, when America entered World War One five years later in 1917, Buckley volunteered for the Army. He was subsequently killed in action in France. In all the lifeboats he supervised the filling of, Lightoller allowed only one man to board. That was Major Arthur Godfrey Peuchen. Lightoller allowed Peuchen aboard because Lightoller had run out of available crew with experience in small boats on open water to pilot lifeboats and Major Peuchen was the Vice Commodore of the Royal Canadian Yacht Club, so the lives of a boatload of women and children were trusted to Peuchen’s maritime skills on the unforgiving surface of the Atlantic.

Other officers, like William Murdoch, allowed men to get into the lifeboats they were loading. Murdoch took women and children first but reasoned, if there was room and there were no more women or children, why not let men on a lifeboat? Bruce Ismay, the President of the White Star Line, bullied his way onto a lifeboat. That action later brought approbation and followed him the rest of his life. He resigned his position as President of the White Star Line the next year and went to live in seclusion in Ireland where he died in 1937. Thomas Andrews, the man who supervised the construction of the Titanic, went down with the ship and drowned. “Mr. Hoffman” did not get on a lifeboat but he put his two sons, an infant and a toddler, in one of the lifeboats in the care of a kind stranger. Mr. Hoffman’s real name was Navatril, and he had stolen those boys, his own sons, from his estranged wife who he considered to be an unfit mother. The boys were reunited with their mother sometime later, after the survivors landed in New York.

At 2:20am on April 15, 1912 the Titanic slipped beneath the surface to its watery grave. Most of the passengers were left to do the best they could with life belts in the open Atlantic in 28 degree water. Olaus Albeseth was one of the passengers who was made to swim for it. Some passengers, like Albeseth, swam to lifeboats that weren’t full and pulled themselves aboard. Olaus Albeseth survived and farmed his homestead in Perkins County, South Dakota. Eventually he moved to Harding County where he died in 1980 at the age of 94. He’s buried in Glendo Cemetery in Ralph, South Dakota.

Only Fifth Officer Harold Lowe took his lifeboat back for those in the water. He managed to save four people. He picked up several others too, but they were too far gone and died in his lifeboat from exposure. The other 17 lifeboats did nothing, despite the urgings of many of the women in the boats to try and rescue those in the water. Some feared desperate swimmers would capsize the lifeboats thus killing everyone. The experienced sailors piloting the boats knew how cold the water was and how little chance anyone in the water would have, even if they were rescued from the Atlantic’s icy depths. So, people sat in the boats, surrounded by the thrashing of swimmers trying to stay afloat and the cries for mercy, deliverance and agony of those dying all around them.

The survivors in the lifeboats reported hearing the eight piece orchestra playing until the very end. The last song they remember hearing was the English hymn “Autumn”. More on the band in just a bit.

Because of the Titanic’s sinking, there were hearings and investigations on both sides of the Atlantic. Many reforms were adopted because of the catastrophic loss of life due to the Titanic disaster. Of the 2,240 people on board only 706 survived. SOS became the standard distress signal and ships at sea were required to man their radios 24/7. Ships that heard a SOS signal were now obligated to respond if at all possible. Ships were required to carry enough lifeboats and life jackets for everyone on board, passengers and crew. There is now an International Ice Patrol made up of ships from both Britain and the United States (in the US it is patrolled by Coast Guard vessels). These International Ice Patrols monitor ice floes, warn other ships of iceberg danger and even carefully shepherd some bergs out of the shipping lanes.

About two weeks after the sinking of the Titanic, the family members of the band received an official letter from the White Star Line. Expecting a note of condolence, instead the families received a bill for 14 shillings and 7 pence (about $4 in 1912 dollars which would be equivalent to $128 today) for the uniforms and other kit of the band members. Outraged, the familes went to the press which printed copies of the bills in Britain’s newspapers. The White Star Line quietly dropped their claim against the families of the deceased band members.

The Titanic, the evening of April 14 into the early morning hours of April 15, 1912 – A Night To Remember.